Podcast Ep 167: A tech pioneer, a bestselling author, a successful entrepreneur, and a billion-dollar intellectual property (IP) coach, Raymond Hegarty is powered by curiosity. The start-up and scale-up journeys, he says, are not for the faint-hearted.

There are few people in the frenetic world of IP who don’t know Raymond Hegarty.

Hegarty is an Irishman who happens to be one of the world’s leading authorities on intellectual property (IP). He is the author of three IP strategy bestsellers – “IP Fantasia”, “Billion Dollar IP Strategy” and “Intellectual Property for Executives” and has managed billions of dollars in patent and trademark transactions. He is also an entrepreneur who has built five successful FDI start-ups for international corporations in Ireland.

“If you’re trying to be acquired, or if you’re going for a significant round of funding, you need to make sure you’re in good enough shape to be able to get through that due diligence. And that’s a huge part of what I do these days working with CEOs”

Hegarty coaches CEOs and CFOs of growth-stage firms to create and execute global intellectual property strategies with a focus on scaling and attracting investment.

An expert adviser to the European Commission and national governments on innovation policy, he has managed billions of dollars of patent and trademark transactions, including signing more than 60 IP licensing agreements with China.

And somewhere in his schedule he happens to be a pioneer in the realm of internet of things, artificial intelligence, telematics, virtual reality, augmented reality and blockchain. He also happens to be fluent in Japanese, French and German and is currently learning Mandarin Chinese.

This geek’s curiosity

How does he find the time. “Well, everybody has 24 hours in the day and the key is time and what you do with it. My whole thing is that I’m just fascinated by so many different things. And my work in the world of IP really does feed this geek’s curiosity, because I get exposed to ideas that happen five years before the rest of the world gets to see them. So that’s really exciting for me.”

Like most of Hegarty’s accomplishments, he kind of fell across opportunities and allowed his curiosity to get the better of him; tempering it of course with hard work and study.

“It was a gradual evolution. I began my career as an engineer. And I worked in international business. And as I said, I had a lot of experience with FDI start-ups. And along the way I studied also. So I studied for business, I studied law. So that combination of the legal, technical and commercial has a very nice intersection where IP commercialisation is well matched to that. So gradually, I moved more into the world of IP commercialisation. And that’s things like licensing, trademarks, licensing patterns. So I’ve worked in the technology industry, and I’ve worked in the fashion industry as well with trademarks.”

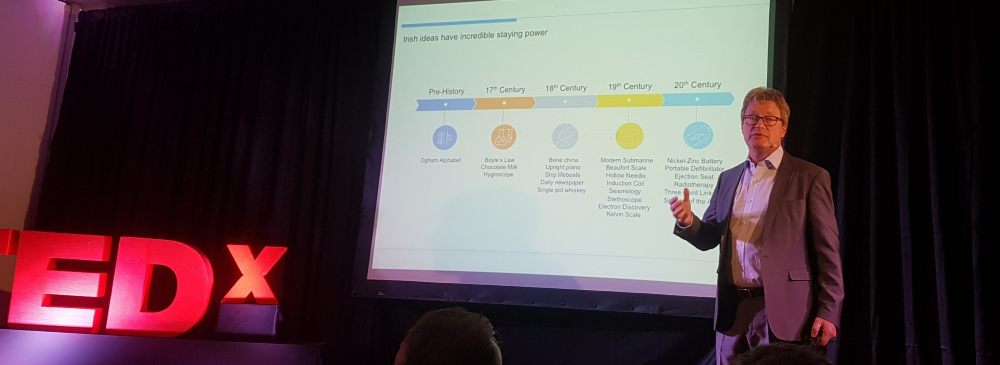

I put it to Hegarty that Ireland is relatively new to the IP world. Despite the success of Science Foundation Ireland’s strategy of the past 20 years to create various centres of excellence and grow the PhD population, as well as Ireland’s FDI success of the past 50 years, as a nation we have had to do a phenomenal job of catching up with the rest of the world.

“Yes, we certainly are seeming to be punching above our weight. For a country, the size of Ireland, the fact that we have such a global footprint. You said that we were poor in the 1970s. But one thing we were rich in and we didn’t really appreciate, we took very much for granted, was that we were rich in the population of young, well educated workforce, and a young educated workforce that was curious. And ambition continued to grow with the country as well. The IDA were way ahead of nearly any other country’s authorities in the industrial policy and economic policy of attracting in foreign direct investment into the country. So the young, well-educated workforce, combined with the multinational influence, where you had a lot of companies coming in here, gave exposure to this young educated workforce.”

Hegarty says another ace up Ireland’s sleeve has been the Diaspora and the strength of the Irish connection, manifesting in the access Irish politicians get to the White House every year on St Patrick’s Day. “No other country gets that kind of access to the White House on their national holiday. Those are amazing things, and we shouldn’t take them for granted. And we shouldn’t get too arrogant about it. We still are a small country. And we have to appreciate all of the benefits that our relationships with the US, but also with other international during our part of being part of the EU, our relationships with the UK, relationships with faraway places like Japan, China, Korea, all of those things.”

In effect, Ireland hasn’t just played catch-up, it has played leap frog in Hegarty’s estimation; vaulting from low-level manufacturing activities to today some very high-level activities in the fields of tech and biotech, for example.

“That was what the IDA really did bring to Ireland in the 1960s 1970s 1980s. Apple came to Ireland as a manufacturing company. So that was a very strong endorsement of the move to secondary industries. And then it continues to today a lot of the activities that Apple is doing in Ireland now are up in the more creative level. So you’re now moving into the primary industry. There is this move towards knowledge and IP, which is my area.”

Layers of substance

Hegarty himself came from a manufacturing background which set him on the road to becoming a global authority on IP and in many ways this was prescient.

“It was about substance. An intangible substance seems like an oxymoron. I came from manufacturing so I understood substance, especially as I was working in the multinational environment in Ireland where we really did have to prove that we were manufacturing in Ireland, that we were an Irish company and that the Irish regimes applied to us. So we were very careful about making sure we were doing all the correct things about Irish substance from manufacturing. And then as I moved over more to the intangibles, intangible substance has become a very important area as well if you look at OECD BEPS (domestic tax base erosion and profit shifting), which was a project to reduce the shifting of tax activities to different environments.

“The easiest way to shift to a jurisdiction would be to assign your IP to a different jurisdiction. The OECD tightened up those rules and they are also looking at intangible substance, which is an area I ended up writing about in a chapter in the Tolley’s Tax Guide, which is on the desk of every tax professional around the world on the concept of intangible substance in the context of the OECD BEPS. And this is something that is really coming to the fore now in Ireland.”

Without getting bogged down in the whole tax argument around Apple, the EU and Ireland, Hegarty says the situation is much more nuanced than portrayed in the media or by politicians.

“If you take a situation of multinationals based in Ireland, very often, you will get unfair sound bites, which are thrown out. And the unfair sound bites can be very sticky. Whereas the reality can be much more nuanced. And it can be actually the exact opposite of what is conveyed in those sound bites. So you’re correct that some of the messaging that got out has been unfair. And it’s balanced by the tax authorities in the different jurisdictions all wanting to make sure that companies are paying their fair share. So there’s that balance of the tax authorities trying to make sure that companies are paying their fair share and companies who, like Apple, was very clearly was following all of the laws. And the question is, where some of the laws were the unintended consequences of some of those laws.”

Starting and scaling

On the subject of entrepreneurship and starting successful FDI start-ups, Hegarty said that an FDI start-up is a very different animal from your average start-up.

“I’ve run five FDI start-ups in Ireland over the decades. The big difference between the FDI start-up and what people have a traditional idea of a start-up is that they’re coming from a very successful parent company. And the parent company has resources that has reputation that’s got proven market, it’s got proven capabilities. And now they want to try and see if they can replicate the same thing or build on that from Ireland. So you are starting with some kind of a playbook that you can reference with an FDI start-up, and you’re coming with resources, you might even come with market relationships that the parent company has helped you with as well.

“So all of those things do give a very good head start for those start-ups. We weren’t the type of start-ups we see now. A lot of them are very scrappy. They have no resources, and they’re having to be resourceful to try and see how can they take what they have an build something from this, and it might be an unproven model. You might not have a market yet, you might have customers difficulty attracting talent when you’re competing with those very large multinationals who are very good to have on your CV, and also they might be paying better as well.”

Speaking to ThinkBusiness.ie ahead of a Bank of Ireland event aimed at scaling tech businesses, Hegarty says the challenges are different for scaling firms.

“A difference between them and the start-ups is that they have come through the start-up phase, they have been de risked, largely, because they’ve survived this long, because a lot of the start-up companies fail. These are companies who have survived, and they have ambition. So they want to take it forward. So with start-ups, very often, you go through the first phase of trying to work out what you’re going to do and how you’re going to do it. The next phase of it is that you’re getting worried, you know, put somebody else copy you because very few barriers to copying what you’re doing.

“Because if you were scrappy, somebody else was scrappy, or somebody else is even a little bit better funded, they could come and take it all away. So as a start-up, you’re worried that somebody’s going to copy you, as a scale up very often, you’re not even as much worried about people who are copying you, as people who are going to get in the way of your scaling. And that can be some of the bigger players who may see you as a threat. And they may try to suppress this threat.

“So it’s very important at that stage not to be using your IP just to protect and stop the garage next door from copying you, or the garage in China if you’re more sophisticated. But you’re now looking at how am I going to take this forward? Am I doing anything that could be infringing on other people’s IP is a serious consideration. And then you’re looking at things like trade secrets and how you handled the movement of talent, both into the company and out of the company. And all of those issues are very regular day-to-day issues for the founders of scaling companies.”

Behind the myriad stories about acquisitions of Irish tech firms what no one talks about is running the gauntlet of due diligence.

“I was talking to Mark Little who’s had two exits. And he, I asked him about due diligence, and he stopped and he said ‘Oh, my goodness, this is the thing they don’t teach you about in business school’. But he gave the example of when he was getting the offer to sell Storyful to News Corp. From the time that they got the offer from News Corp. To the time they closed, the deal was more than nine months. They were given a stack of questions, which a lot of them were just totally irrelevant to the business, they were asked, you know, how many corporate jets do you have? And he was saying, ‘we didn’t have money to change light bulbs’.

“These are the kinds of questions that you have to answer to the satisfaction of the lawyers who have this checklist approach to what you’re doing. And the difficulty is, if they come across something, which could be problematic, it will either reduce the price of the acquisition, or it will kill the acquisition. So it’s something that when you’re making an acquisition, you need to make sure that you do due diligence, that you’re not getting some kind of a problem with it. But if you’re trying to be acquired, or if you’re going for a significant round of funding, you need to make sure you’re in good enough shape to be able to get through that due diligence. And that’s a huge part of what I do these days working with CEOs.”

He says the stress of due diligence with the clock ticking as your business runs out of runway financially, is something many successful CEOs are haunted by, no matter how successful.

“And if this deal doesn’t work, you might not be there to be able to pick up the pieces and run with the company again. So when a lot of people come to the end of this – the news headlines all look like a victory and success – rather than a feeling of elation, a lot of the founders have this feeling of relief, that they just came out of this. And they are just ‘oh my goodness, am I still alive after all of this?’”